CO - Chemins de fer Orientaux

CO History

After the Crimean war, the Ottoman started an internal debate about the opportunity of a rail link from Istanbul (Constantinople then) to Western Europe. Such a land bridge would greatly facilitate transportation of troops in this area. It would also facilitate trade between the Ottomans and Europe and would provide an alternative to the near monopoly of British sea transportation. In the other hand, this railway would bring also Austrian influence to the Empire outer territories and perhaps encourage these territories to secede.

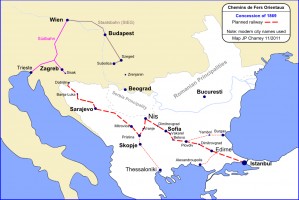

Hirsh concession

Under this background of mixed opinions, the Sultan finally awarded a concession to build a railway from Istanbul to Vienna on May 31, 1868 to Van der Elst and Cie, a Belgian company. Subsequently, Langrand Dumonceau, a French entrepreneur who helped in negotiating the concession, took over the concession from Van der Elst. However, Langrand entered himself into financial difficulties and could not fulfill the concession, which was cancelled by the Ottomans and April 12, 1869. The concession was picked up on April 17, 1869 by Baron Maurice de Hirsh, a German born financier (1831, 1896). Hirsh was in partnership with Langrand on several other railway ventures in Europe.

The concession included a main line from Istanbul to the Austrian border (at Dobrljin) via Edirne (Adrianople), Sofia, Niç, Sarajevo and Banja Luka. This is known as the "south road" as it tends to go around Serbia in favor of Bosnia. Serbia, still nominally part of the Empire, was in fact autonomous since 1829 (Adrianople treaty) to the point of being nearly independent. In addition, the connection via Bosnia was sponsored by the Austrians who were trying to place Bosnia into their sphere of influence. The original concession included 3 branches:

- Edirne (Andrianople) to Alexandropolis (Dedeagatch, on the Aegean sea)

- Philippolis to Burgas (on the Black Sea)

- Pristina to Thessaloniki (Salonica)

The total route length of the concession was estimated at 2500 km. The concession was for 99 years. In exchange for the cost of building the line, the concession holder would receive a rent of 14000 Francs per km from the Government and 8000 Francs per km from the operating company. These amounts were calculated to provide a return on investment of 11 percent for the concession holder. The concession contained also specials term:

- to cover the construction period during which the operator could not get full revenue.

- to cover the cost of crossing difficult terrain in Bosnia.

- to provide the Ottoman Government with a share of the benefits should it exceed 22000 francs per km.

The concession was combined with an Ottoman bond issue underwritten by a syndicate also formed by Hirsh. The Ottoman government could meet its kilometric guarantee thanks to the cash thus successfully raised by Hirsh.

Hirsh set up quickly the Société Impériale des Chemins de Fer de la Turquie d'Europe to build the railway. The company headquarter was located in Paris. Among others, the company hired Wilhem von Pressel from the South Austrian Railways to be chief engineer of the project. Construction works started as soon as 1870 despite the Franco Prussian war. Groundbreaking occurred simultaneously in Istanbul, Alexandropolis, Thessaloniki and Dobrjlin. Nearly 500 km of route were ready for operation in 1872.

According to Hirsh original intend, operation of the lines was supposed to be done by The South Austrian Railways(Südbahn). However, negotiation with this company failed and Hirsch had to set up on January 1870 its own operating company: Société Générale pour l'Exploitation des Chemins de Fer Orientaux (CO), also headquartered in Paris.

Concession dispute and settlement

In September 1871, following a government change, the new grand vizier Mahmud Nedim Pasha started to renegotiate Hirsch concession. The Ottoman aim was to delay further line building and to reduce the drain on the budget caused by the first concession. Through completion to Vienna was no longer a priority.

Under the new agreement signed 18 May 1872, operation of the railways was still conceded to the CO. But the Ottoman government took charge of building all new lines. The works that where on going at the time where now under a subcontracting contract to Hirsh. As a result, Hirsh was no longer reponsible for the completion of the initial network.

In 1874, Hirsh completed the works and the CO was now operating a network of about 1300km three distinct and not conected lines:

- Istanbul to Edirne, Plovdiv and Belovo, with branches to Yambol and Alexandropolis

- Thessaloniki to Mitrovica

- Doberlin (Dobrljin) to Banja Luka

The Dobrljin to Banja Luka line was not connected to the Austrian network and thus did not fullfill any purpose. It quickly generated an operating loss and was dropped in 1876.

The various uprisings in the Balkans (Bosnia 1874, Serbia and Bulgaria 1876 - 1878), the Ottoman debt default in 1875 and then another war with Russia (1876 1878) made further railway building impossible.

Too many curves?

Very early on, Baron Hirsh opponents charged with him with designing a poor network with too many curves in order to increase the actual distance. In turn this would increase the rents paid out by the Ottoman government. In his defense, Baron Hirsh responded that all detailed designs were approved by the Government before construction. In addition, the Government changed the design for military & strategic purpose. He was referring here to the fortifications along the Çatalca Line protecting Istanbul. The line had to be built within gun range of those fortifications.

With modern technology such as satellite pictures, it is easy to understand what happened. In Trakia, the line was built following the two main rivers: Ergene River and Maritza River, following the same altitude lines as far as possible and the expense of curves. Trakia is fairly flat with only soft hills. There are no tunnels and no big earthworks. The only significant climb is between Çatalca and Çerkezköy where the line climbs from 50m to a 200m high summit near Kurfallı at an average grade of 6‰ which is quite low by Turkish standards. Observers also noticed that some stations are located quite far outside the cities. In all cases, this prime indent was to avoid difficult terrain, bridge building and the like. Everywhere design made the line as cheap as possible to build, reducing capital cost and enabling quicker opening.

Is this bad? Many railways in the world have been built in the same manner, most notably in North America and Russia where builders have used every trick in the book for quick line opening and rebuilding later the worst sections as traffic grew up. However it suited the Ottoman government to play up the low quality of the works in their dispute with Hirsh. This was later amplified by the Republic to vindicate their program to nationalize the railways. The line today is by and large the same as when it was built. Double tracking occurred only in the Istanbul suburb area. The orignial alignement is largely unchanged.

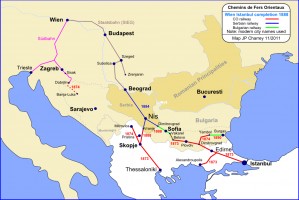

Istanbul to Vienna completion

The Congress of Berlin restored peace in the Balkans and with Russia. Serbia, Romania and Bulgaria became independent and Bosnia Herzegovina became occupied by Austria. The Congress decided that the Istanbul Vienna railway should be completed and created a special committee dubbed "Conférence à Quatre" (Austria, Turkey, Bulgaria, Serbia) to oversee the project. At that time (1878), Hirsch transferred the headquarter of the CO from Paris to Vienna.

Further delay occurred and the Conférence à Quatre could convene only in December 1882 in Vienna. The final agreement was signed on May 9, 1883. It provided for a goal to complete the line by October 1886. The route now chosen was starting from Belovo to Sofia, Nic and Belgrade. Junction with the Autrian Staatsbahn will be in Zemun (Semlin), on the oustirk of Belgrade. In addition, a branch from Nic would be built to reach the Skopje and Tessaloniki . Each government was responsible for the works on its territory.

Construction of The Belgrade Nis Vranje line was won by Paul Eugene Bontoux, a Frenchman. His company "Union Générale" went bankrupt in April 1881. The line was taken over by a group of French and German banks led by "Comptoir d'Escompte de Paris". These banks formed the new Serbian railways: "Compagnie de Construction et d'Exploitation des Chemins de fer de l'Etat Serbe.

Hirsch managed to secure most of the works on Ottoman territory for his company. The construction works proceeded again quickly until Bulgaria moved to occupy Eastern Roumelia, contrary to the Berlin protocol. Bulgaria seized by force the nearly completed line in Eastern Roumelia (Belovo to Vakarel). A new agreement had to be worked out: the Bulgarian State Railways took over the Belovo Vakarel line, finished the work and opened it to traffic July 7, 1888. The first through train between Vienna and Istanbul ran on August 12, 1888. Through running of the Orient Express between Paris and Istanbul started on June 1, 1889.

Meanwhile the junction line between Skopje and Nis was completed on May 25, 1888. The Thessaloniki line was now connected to rest of the network.

Baron Hirsh retires

Upon the completion of the railway, Hirsh decided to retire from business altogether. Under the mediation of Oscar S. Strauss, USA ambassador in Istanbul, Hirsh and the Ottoman government entered yet another round of negotiation to settle all the accounts, including the outstanding Ottoman claims towards guarantee funds held by Hirsh. The agreement was reached February 25, 1889 and Hirsch repaid 60 millions francs to the Ottomans. Having cleared all its liabilities, Hirsch started to plan its retirement after nearly twenty years of railway buildings in the Balkans. In April 1890, he sold the shares of the company to a group of German banks led by the Deutsche Bank.

The Deutsche Bank viewed the CO as a strategic acquisition towards its goal to realize the Baghdad Railway. The CO was a perfect complement to the CFOA then under construction. CO ownership was transferred to the same subsidiary of the Deutsche Bank that already owned the CFOA: the Bank für Orientalische Eisenbahnen, headquartered in Zürich.

The Deutsche Bank also acquired the concession of the Salonique Monastir railway on 28 October 1890 and gave the operation of this railway the CO. Finally, the Deutsche Bank acquired in 1895 a 30% share of the Chemins de fer Jonction Salonique Constantinople. This was a strategic move to shield the CO against issues in Bulgaria by having an alternate route to Serbia.

Balkan wars

Balkan wars (1912 and 1913) brought about several major border changes including the temporarily loss of Edirne in 1913. The European part of the Empire was reduced roughly to the present situation for the benefit of Serbia, Greece and Bulgaria and Austria. Subsequently, ownership and operation of railway lines lying now in Serbia, Greece and Bulgaria were transferred to their respective state railways. The CO was shortened basically to the Istanbul Edirne line.

The only major extension build during those trouble days is the 45km branch to Kırklareli in 1912.

First World War to Lausanne treaty

During the First World War, the CO came then under special military command. Needless to say that the CO was of special importance to move German troops and equipment across continental Europe. The World War was then followed by the Independence War.

Peace was restored and border finalized thanks to the Lausanne Treaty in July 1923. In accordance with the earlier Bulgaria Turkey treaty (1913), the border was placed between Greece and Turkey along the Meriç Nehri river (also known as Maritza or Marika river in Bulgaria, and Evros river in Greece) except for the city of Edirne, which remained Turkish. The original CO line which was on the west bank of the river crossed therefore the new border three times:

- just before and after Edirne Karaağaç station

- after Pythion where the bridge across the river is located to reach Üzünköprü in Turkey.

Following the provision of the Versaille treaty regarding German assets abroad, the CO could not stay under its present ownership. The solution came in 1929 in the form of a split:

- the Greek bit of the line, including the 10km or so on Turkish soil to reach Edirne was transferred to a new company: Compagnie de Chemin de fer Franco-Hellenique (CFFH). The CFFH is set up as a French company with headquarters in Paris

- the Turkish part of the line stayed under the operation of the CO, whose ownership is taken over by a consortium of French entrepreneurs.

The border between the CO and the CFFH was placed along the state border, between Pythion and Uzunköprü.. The CFFH survived as an independent but hardly profitable entity until the Greek State Railways absorbed it on 1 January 1955.

The cumbersome border crossing situation at Edirne lasted until 1971 when TCDD opened a 73km direct line between Pehlivanköy and the Bulgarian border at Kapikule. This line includes a new station at Edirne, north of the previous one.

The Greek State railway built also a short cut-off between Marassia and Nea Vissa to avoid Turkish territory near Edirne. This resulted in the abandonment of the former CO Edirne magnificent station.

The CO was nationalized by the Turkish Republic when the Government bought the company on 25 December 1936. The capital cost was 20,6 million Swiss Francs and effective transfert to TCDD was on 1 January 1937.

CO lines opening dates

This table indicates only the CO lines currently in modern Turkey

| from | to | Original company | Opening year | Opening date | km | miles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yedikule | Küçük Çekmece | CO | 1871 | 4 Jan 1871 | 16,6 | 10,4 |

| Sirkeci | Yedikule | CO | 1872 | 27 July 1872 | 4,7 | 2,9 |

| Küçük Çekmece | Hadımköy | CO | 1872 | 22 July 1872 | 30 | 18,8 |

| Hadımköy | Edirne | CO | 1873 | 4 Apr 1873 | 236,8 | 148 |

| Kırklareli | Alpullu | CO | 1912 | 19 June 1912 | 45,5 | 28,4 |

One of CO Hanomag loco in front of the Imperial Military Medical School. This school was located just behind the CO track, near Sirkeci station. The turntable was removed during the electrification works in early 1950's. The Medical school in the background still stands, however the building shape changed when a slopped roof was added. Photo Abdullah frères, 1890, Abdul Hamid II Collection for the Library of Congress.

| Quick jump to: |

|---|